Within the last few years visits to a unique silk museum, and also England’s most famous burial plot, have helped me to unravel a fascinating story which I want to share with you. There cannot be much doubt that the taste of France is represented by the truffle, the Camembert cheese and the hideously produced paté fois gras. The English equivalents might be mushy peas, black pudding, and the Melton Mowbray pork pie. But I have to say that my personally favourite bit of Englishness is Hovis bread, with butter spread so thickly that you can see teeth marks. Now, if you want to turn a success into a triumph, finally add a cataract of Marmite. How many people enjoying this delicacy know anything about the history of Hovis? The first thing you need to do is travel to Macclesfield, once the centre of Britain’s silk industry and which still has a highly recommended Silk Museum. The second thing you need is a working knowledge of Latin. Finally you must appreciate that a grain of wheat is not just a grain but in reality rather a complicated structure.

The ‘germ’ of the wheat is the embryo plant. Most of the wheat grain consists of a starchy endosperm which provides the nutrition for the young wheat while it is learning how to do photosynthesis. Humans have ground the endosperm into flour since Neolithic times. The whole grain is covered by an outer husk which is otherwise known as bran. After the introduction of wheat milling by steel rollers the public demand for white flour led to manufacturers separating out the bran and wheat germ as by-products. The germ contained polyunsaturated fats, which could subsequently lead to early rancidity of the flour, so there was some purpose in this discrimination. However the germ does contain some highly desirable constituents: zinc, magnesium, B vitamins and vitamin E. While deficiency of vitamin E has been linked to neurological and blood clotting problems it is uncertain whether additional supplements have any beneficial results on human health. Some people believe that they do although others including me think that, pharmaceutically, vitamin E is a solution looking for a problem. Anyway it’s there in the germ and some people love it.

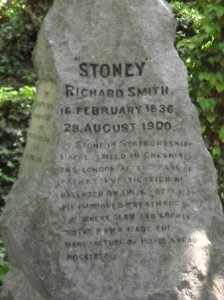

Today there is a movement against the refining of flour and many people feel comfortable with a more traditional brown bread. Bran is frequently, one might say regularly, returned to the flour as a source of dietary fibre. Wheat germ is intimately concerned with the story of Hovis. A miller called Richard ‘Stoney’ Smith (1836–1900) had the brilliant concept of removing the germ, lightly cooking it to prevent future rancidity, and then returning it together with all its B and E vitamins to the flour to be baked into bread. The final product had a unique taste and a beautiful golden-brown colour. I can’t help thinking that at the last moment Smith snatched defeat from the jaws of victory by naming his discovery ‘patent germ bread’. Sadly by that time, 1887, germs were acquiring a new and altogether different meaning, Sadly Smith did not live long to enjoy the fruits of his genius and has occupied a plot in Highgate cemetery since 1890. At the time of his death Smith had just joined the board of Macclesfield millers S. Fitton & Sons, and Fitton it was who launched the product on the waiting world.

Fitton’s took the brave step of changing the name of their revolutionary bread. They ran a competition for a new name which was won by a man called Herbert Grime. Grime is variously described as a London student or an Oxford schoolmaster but it is agreed that he won £25 for his suggestion. We can imagine various Latin expressions flitting through his mind as titles for wheat germ bread: carpe diem, ad hoc, in loco parentis and then finally hominis vis – feminists please look away now – the strength of man. A little contraction and juxtaposition might easily have resulted in the name Ominir but actually produced Hovis. Shortly afterwards the Hovis Bread Flour Company was born.

Nobody can deny that the company had an impressive product to sell but on several occasions over the last century Hovis has been lucky, or wise, enough to be associated with some innovative advertising campaigns. For many years, like the adverts for bracing Skegness, it was associated with railway companies. Then in 1973 a new star was born. Ridley Scott was a little known film director, with Alien only a glint in his eye, when he was taken on to advertise Hovis for Rank McDougall Hovis, its then bakers. He produced images of a boy on a bike riding through a picturesque village to the music of Dvorak’s ninth symphony. The voice-over, and the brass band playing, suggested a gritty northern town although Shaftesbury in Dorset was actually selected as the location. The advertisements most cleverly evoked a time in the golden past when you could catch a tram into town, meet your girl at the cinema, buy both of you fish and chips, and still have change from a farthing. Fiction but powerful fiction.

The advertisement was used for many years but if this wasn’t enough in the new millennium the Hovis makers, by then Premier Foods, produced ‘Go on Lad’ one of the most successful TV advertisements ever made. In the video a boy starts in 1886 and moves forward in time through two world wars to the present day, accompanied by his ever reliable Hovis loaf. It was a brilliant piece and reversed the declining fortunes of the brand. The rest is history.

Oh yes. I say, I say, I say, what did the traditional baker call his daughter? Emmer. But as you can see Emmer is Miss Spelt.

Excellent piece as always!

LikeLike

I’ve never heard of a “cataract of marmite”. I write as a liker of the stuff, and wonder if this is a new method of portion control?

LikeLike

OK it is doubtful if you can have a cataract of a high viscosity product like Marmite. But it’s great on buttered Hovis.

LikeLike